Sneha Shrestha: Ritual and Devotion

Solo show curated by Dr. Rachel Parikh, Cantor Gallery, Prior Performing Arts Center, College of Holy Cross

Feb 1 – April 5, 2024

Sneha Shrestha: Ritual and Devotion is the artist’s first major solo exhibition, which explores the concepts of ritual and devotion beyond the sacred to include the secular. Here, through her immigration journey, Shrestha reflects on what devotion means to her with respect to family, culture, heritage, ancestry, and self, and how acts—such as filling out immigration forms to the actual process of creating her art—can become ritualized. These works, including two site-specific installations, capture the intermingling of the sacred and the secular, and how her immigration journey, its sacrifices, invocations of nostalgia, evolution of identities, and creation of new opportunities continues to shape the artist’s interpretations of ritual and devotion.

Celebration Series

2023

Acrylic and oil pastel on canvas

61.0 x 45.7 cm.

Top, from left to right: “Untitled 1” to “Untitled 10”

Bottom, from left to right: “Untitled 11” to “Untitled 20”

Each of the 20 paintings in this series reflects Shrestha’s immigration journey, which spanned over a decade. They contain the names, written in Nepali, of some of the immigration forms that she needed to fill out. The letters are also superimposed within each canvas, signifying the repetitive nature of filling out these forms, which Shrestha likens to performing a meditative ritual. Through each painting’s palette, Shrestha comments on how the intense process also meant sacrificing time with her family; the colors represent those of the garments worn by her mother during celebrations and holidays that Shrestha missed at home in Kathmandu.

By emphasizing the challenges and difficulties of the immigration process, Shrestha also implies the resilience and courage it takes to go through it. She intends this series to be a celebration of immigrants and their journeys, which contrasts to the negativity and shame that is often associated with it.

Dwarpalika (Temple Guardian) is inspired by different architectural elements that can be found throughout Shrestha’s hometown of Kathmandu. The title refers to female divine beings that guard the entrances to Nepali temples. The arched shape resembles the doorways of these revered and sacred spaces, while the patterned composition alludes to a jali, a type of window distinct to South Asia that is notable for its pierced and latticed screen. The openings allow for light and air to pass through while the structure shields from elements like the harsh sun and rain. In Nepal, it is known as an ankhi jhyal (“window for the eye”). Here, to create the lattice, Shrestha repeats the first letter of the Nepali alphabet, “ka” (क). Like her murals, Shrestha’s sculptures play with surfaces and patterns to transform the space they are created for.

The metallic finish of the sculpture alludes to the final process of bronze casting, which is to highly polish a work so that it resembles gold. It is a technique that is used in the creation of statues of Hindu deities and Buddhas across South Asia, which can be found in homes, storefronts, and temples, as well as Nepali shrines and temple architecture. Gold also has personal meaning for Shrestha, as it reminds her of her mother and the jewelry she wears, in addition to the artist’s iconic gold necklace featuring her mother’s name.

Dwarpalika (Temple Guardian)

2023

Steel and brass (copper alloy)

182.88 x 152.4 cm.

The exterior of the Patan Palace Museum featuring ankhi jhyal. Patan Durbar Square, Patan, Lalitpur, Nepal, 1734. Photo:: Sneha Shrestha, 2022

My Ancestors' Voice

2023

Acrylic ink on canvas

152.4 365.7 cm.

Traditional Nepali manuscripts have greatly inspired Shrestha’s artistic oeuvre. Produced between the 5th and 19th centuries, these historic works—which are typically comprised of Hindu and Buddhist texts—are distinguished by their horizontal composition, neatly and precisely executed text in Devanagari script, and exquisitely detailed illustrations. The dimensions and composition of this painting are evocative of traditional Nepali manuscripts, while Shrestha’s bold, deliberate brushstrokes and accentuated calligraphic style challenge the general misconception and opinion that Devanagari script cannot be revered for its aesthetic beauty.

The painting itself is a collection of letters written in Devanagari. A reader of Nepali, Hindi, and Sanskrit would recognize the letters, but would not be able to decipher the text because it does not say anything. This is the artist’s commentary on the fact that most Nepali manuscripts in western museums are overlooked and remain untranslated.

Unidentified Artist. Illustrated Sutra, Nepal, ca. 1700, ink and pigments on paper. Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of Philip Hofer: 1984.429.1. Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Worlds Apart

2023

Acrylic and oil pastel on canvas

122 X 183 cm.

Although the sea of Nepali letters on each panel seems to be identical and symmetrical, upon close inspection, their composition and content are slightly disparate. This is Shrestha’s way of acknowledging that while she, and other immigrants, occupy two worlds at the same time, they will never be exactly the same. Through this diptych, Shrestha navigates how her immigration journey has placed her in two worlds: Nepal and the United States.

These worlds will always represent different homes, circles of friends, systems of support, cultures, and lifestyles. However, despite these differences, these two worlds can harmoniously co-exist, which the letters on the panels signify by flowing into, and integrating with, one another. The bold, sweeping strokes that go beyond the canvases refer to how one’s immigration journey is never-ending, as one’s life and identity is always changing.

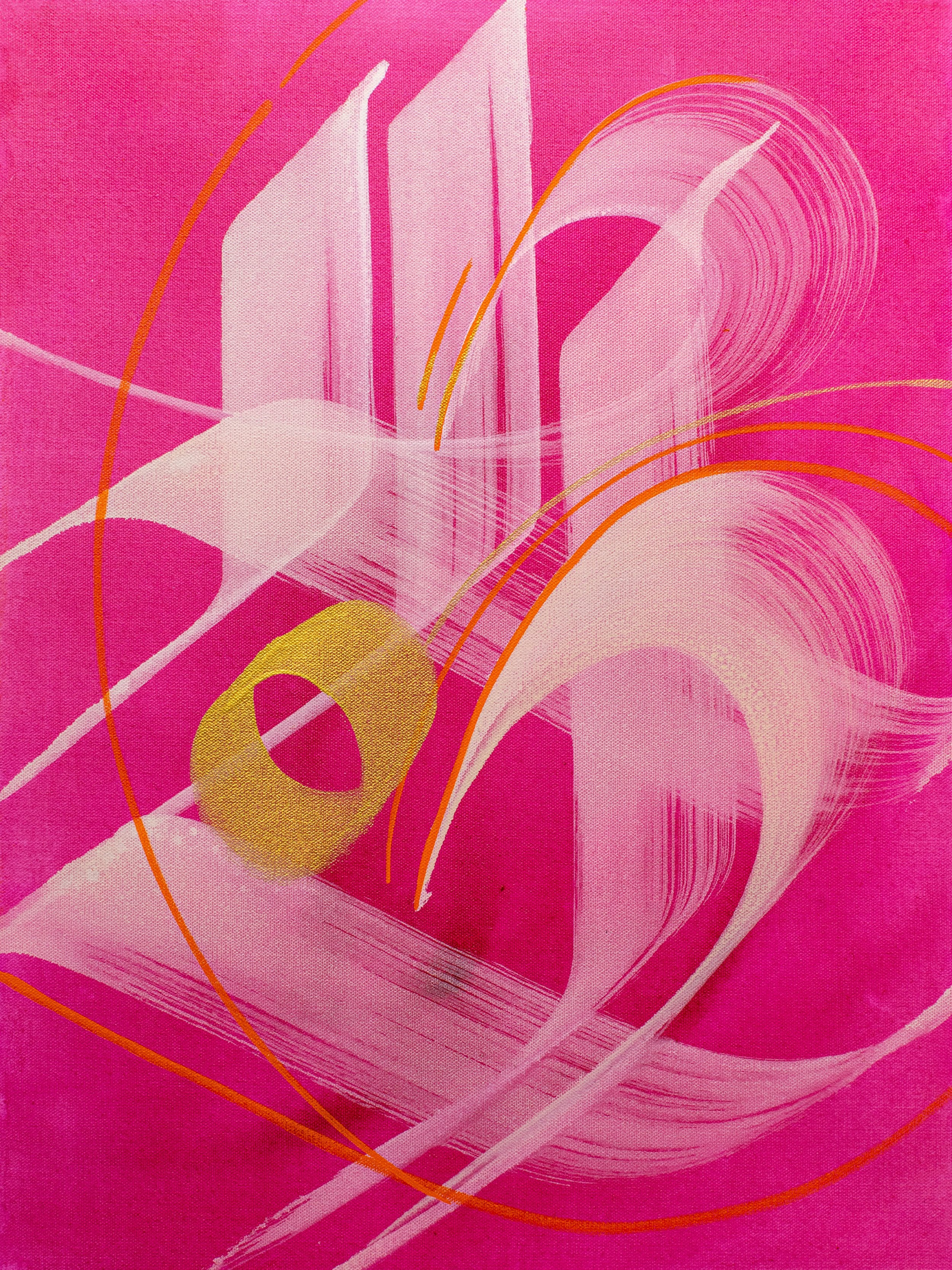

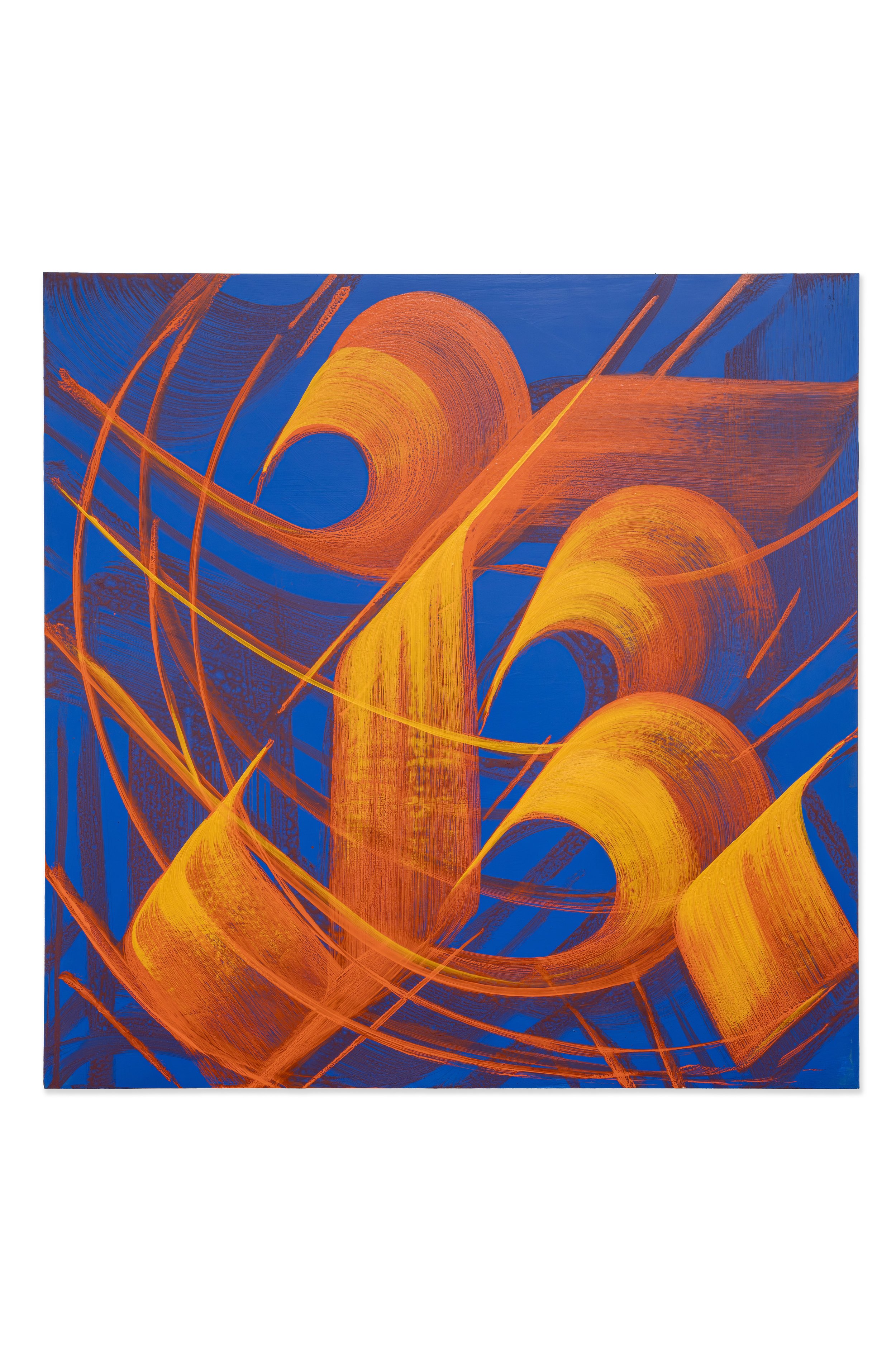

“Devi 7” (left), “Devi 8” (center), “Devi 9” (right), Devi (Goddess) Series

2023

Acrylic on canvas

229 x 152.4 cm.

This large-scale series, considered a subset of the Celebration series nearby, examines the challenges of immigration and its process. It is a comment on the artist sacrificing time with her family, who still resides in Kathmandu, and missing celebrations, such as birthdays, festivals, and religious holidays. Each work contains the names, written in Nepali, of some of the forms Shrestha needed to complete for her immigration process. These names are arranged to allude to a shrine or the gold decorations used during religious festivals. At the top of each painting’s composition is a chandrama, a symbol of an upturned, crescent moon with a circle in its center that is drawn during auspicious occasions.

The series also serves as a dedication to her mother; Devi (“goddess” in Sanskrit) is her mother’s middle name. The colors of each painting are drawn from those in the clothing worn by Shrestha’s mother during Tihar, the Nepali version of the five-day Hindu festival of Diwali. The large, gold strokes signify her mother’s tenacious energy, which the artist channeled during her immigration process. Their expanse beyond the canvases conveys the energy’s boundlessness while also serving as a nod to the colossal presence of Shrestha’s multi-story mural paintings.

left to right: Untitled 10, Untitled 1, Untitled 11, Untitled 12, Untitled 14

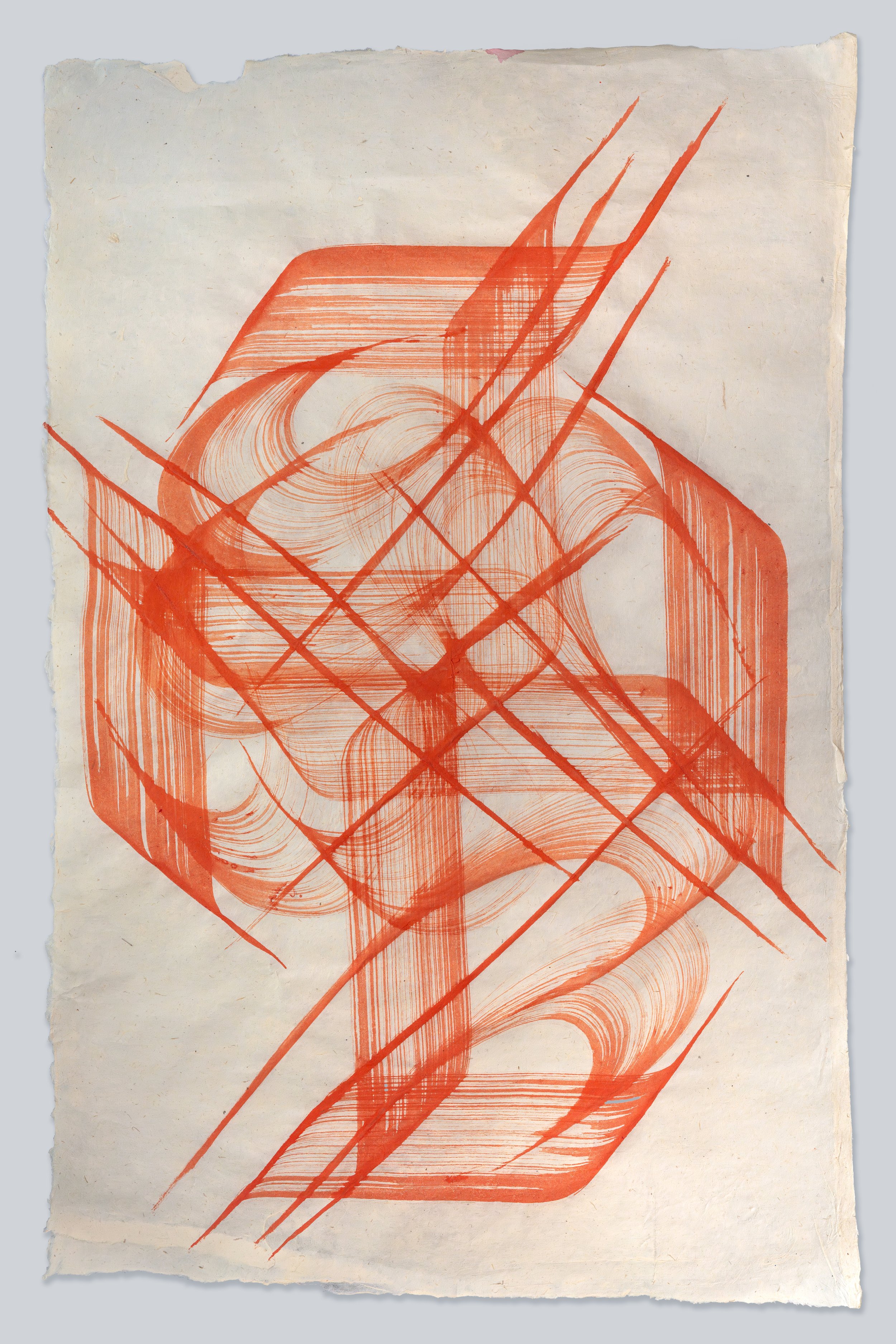

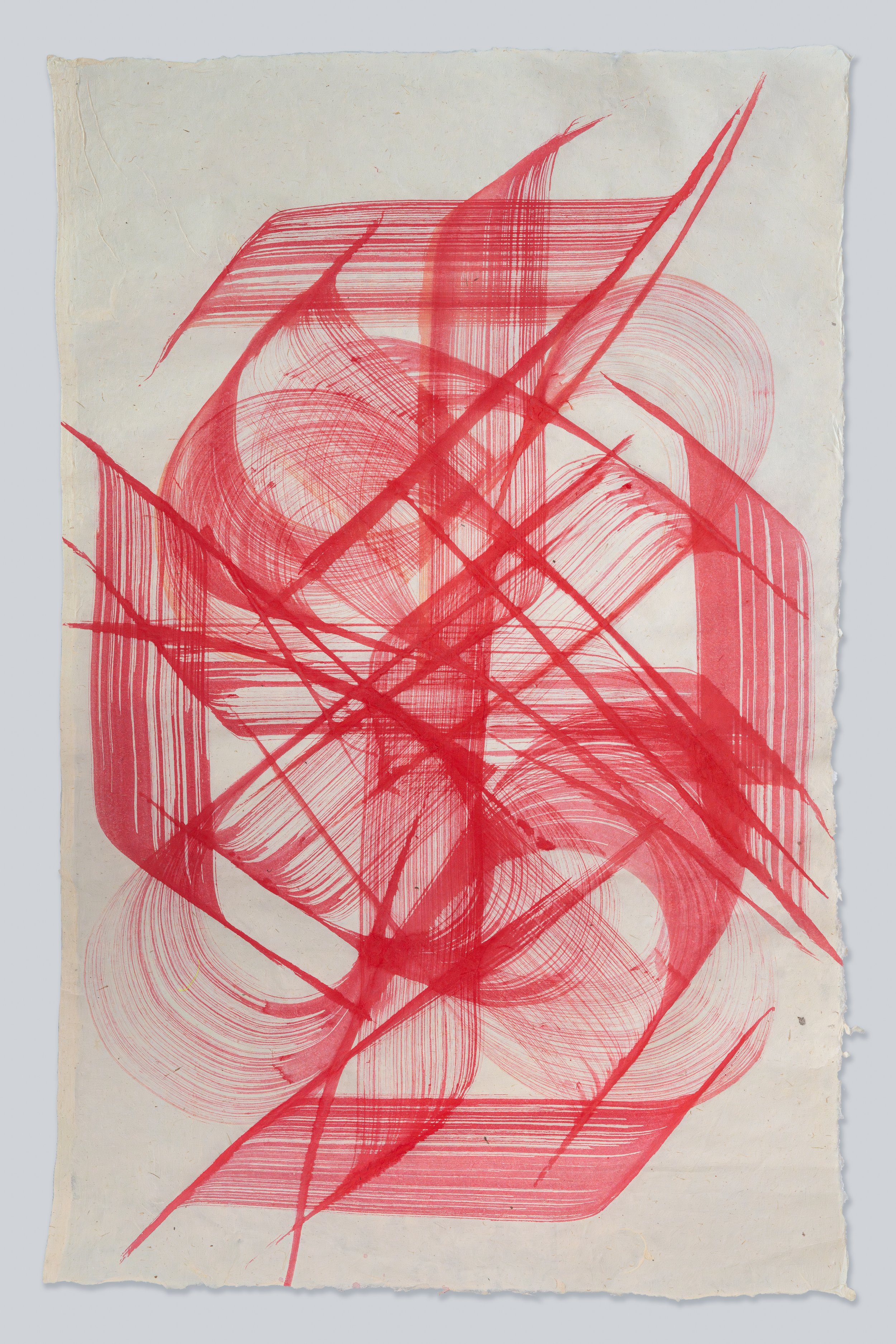

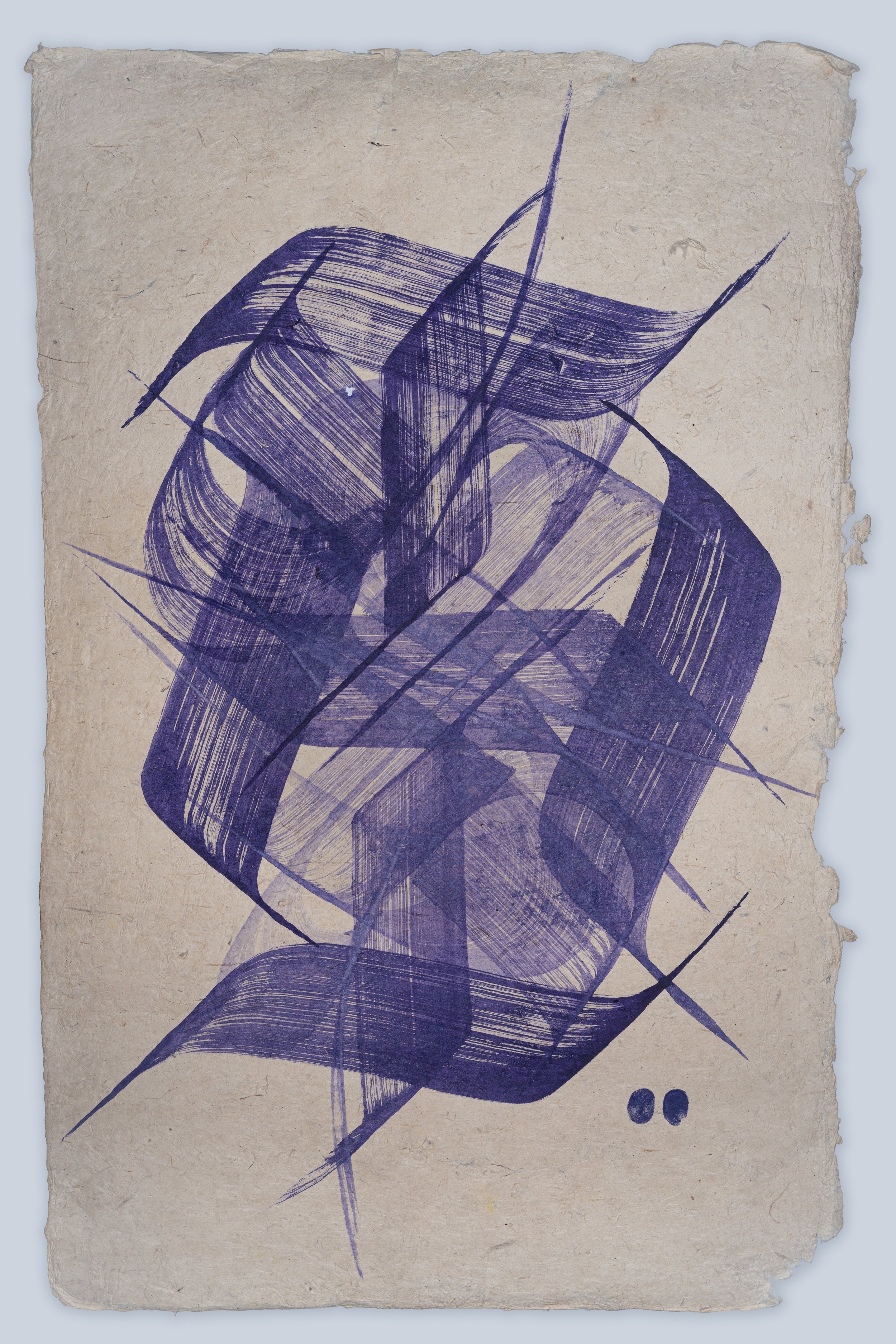

from Home, Too

2020

Ink on handmade Nepali paper

Approx. 76.2 x 50.8 cm.

A mandala (“circle” in Sanskrit) is an artistic representation of higher thought, taking the form of a geometric configuration of symbols. It can be used for focusing one’s attention, as a tool for spiritual guidance and meditation, and to denote a sacred space. Both its creation and result play important roles in Hindu and Buddhist ritualized practices. In each of these 5 paintings, Shrestha creates her own mandala by repeating a single Nepali letter and organizing it into a motif. Her process itself is even meditative; she executes her precise brushstrokes with the regulation of her breath, which affects the symmetry of each design.

Here, Shrestha extends the concept of the ritual from being religiously sacred to being a personal one. The series is painted on paper that is handmade in Nepal and can be found in a paper shop in an old part of Kathmandu where her father grew up. The artist and her father will often travel through the bustling, narrow streets on his motorbike to acquire rolls of this precious material. It is a pilgrimage that signifies devotion in many forms, including to one’s family, one’s heritage, and one’s craft.

These paintings specifically refer to her mural, For Cambridge, With Love from Nepal (2018), a sixty-foot-tall work that is in Central Square, Cambridge, MA. The paintings act as close-ups of the mural, providing a more intimate experience with the larger-than-life work, as well as the opportunity to appreciate, through every curve and angle, the beauty of Devanagari script. Each painting features one to two Nepali letters, such as “ka” (क), “kha” (ख), and “ga” (ग), which are executed with the same tools the artist uses when painting her murals, including an eight-inch-wide brush.

The Nepali Alphabet (1-5)

30”X30”

Acrylic on panel

Devanagari Script

Devanagari (Sanskrit, translates to “divine city script”) is a syllabic script in which Sanskrit, Prakrit, and other South Asian languages, such as Hindi, Marathi, and Nepali, are written. Early use of the script began around the 7th century and it reached maturity by the 11th century. It is written from left to right, and is characterized by symmetrical, rounded letters within squared outlines. It has a distinct horizontal line, known as shirorekha, that runs along the top of full letters.

Rubin Museum Installation

Mending and Moving my immersive installation at the Rubin Museum’s “Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now”

March 15 – October 6, 2024

Inspired by my experiences viewing Nepali ritual objects in U.S. museums, "Mending and Moving" is an immersive installation that questions the spiritual nature of ritual objects when they are taken out of their place of heritage. The installation is divided into three distinct sections: The Mending, The Yellow Room, The Pink Room.

The Mending

As a ubiquitous element of Kathmandu’s architecture, the Toran immediately caught my attention in its incomplete state in the museum display. Here, I have "mended" the missing bottom half with my letters, symbolizing a personal attempt to restore its integrity. <3

The Yellow Room

In this section, I juxtapose the museum’s ritual objects with those from Nepal, sourced by my mother for our family home. I chose to display both sets of objects in the same manner; encased in glass and on identical pedestals. This decision prompts visitors to ponder the difference between objects that are still spiritually active and those whose spiritual essence may have faded.

The yellow room captures the mixed emotions I experience when encountering Nepali ritual objects in museums. Initially, there is a sense of familiarity and excitement, quickly followed by a profound despair as memories of similar objects in my Kathmandu home flood my mind—objects adorned with tika, rice, flowers, soot, and oil as opposed to the now lifeless museum objects, sterile and shiny. This emotional journey is what I aim to convey to visitors.

The Sukunda (Oil Lamp)

The Sukunda is an example of an object that evokes deep cultural pride. Whenever I see it in museums, I proudly recognize it instantly, reassured by the fact that its core design has remained unchanged for centuries. Our traditions endure, as evidenced by the nearly identical Sukunda in my family home and in the homes of many in Kathmandu.

So I wonder: Do the spiritual nature of these museum objects live on? What happens to ritual objects when they are no longer used in rituals? Then, are they still ritual objects?

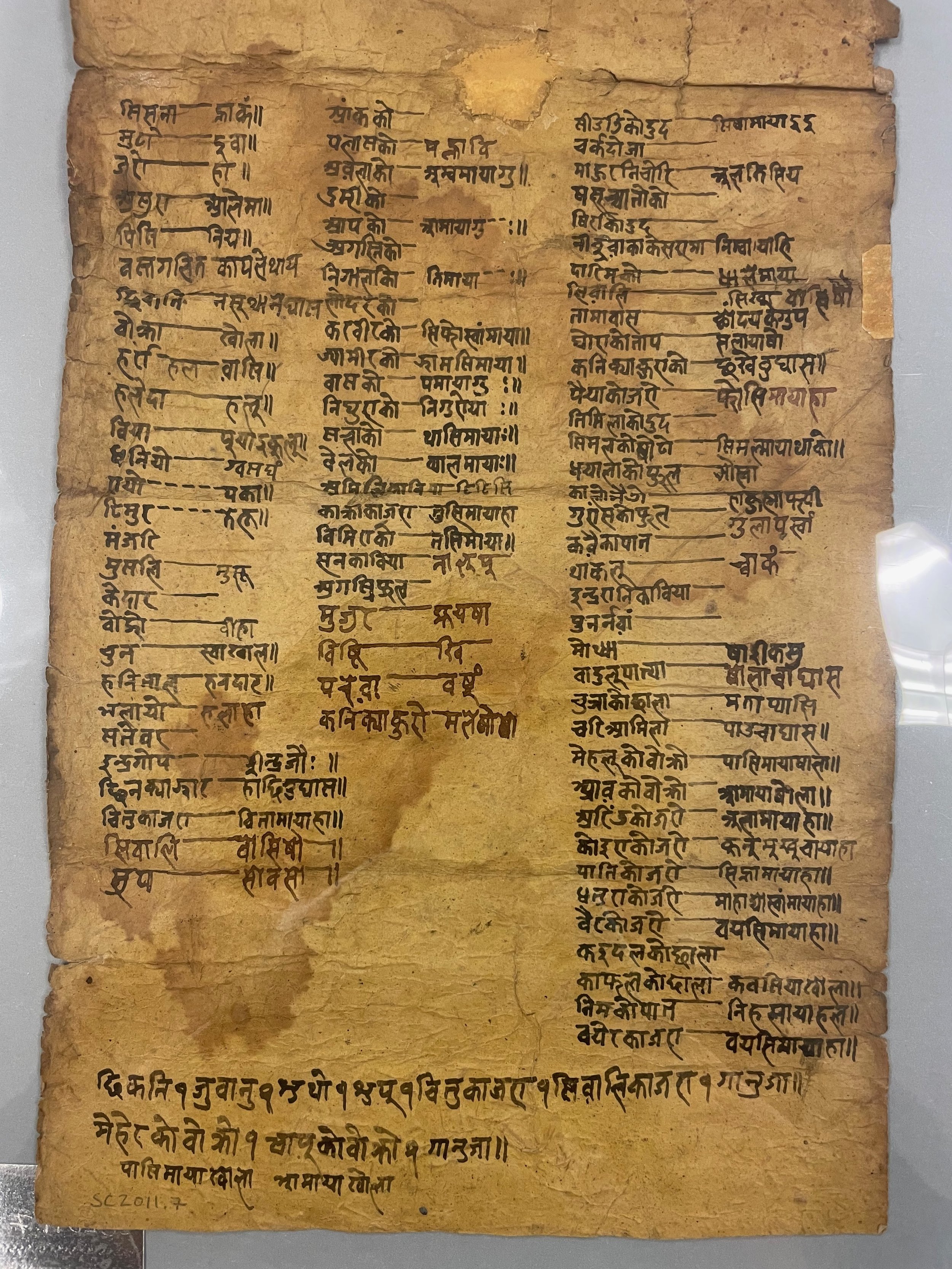

I came across this manuscript when visiting the Rubin to look at some Nepali ritual objects. The vertical orientation of it first made me curious because most of the manuscripts I look at are 14th century horizontal ones. The second is, upon a quick glance without trying to translate the letters, the long horizontal lines made me think of if it was some sort of a list… Upon closer inspection, I found the names of a few foods in Nepali and my first thought was - is this some kind of a menu? At the moment, this manuscript remains untranslated. This is why I titled it The Menu, as absurd as it sounds. Now that I’ve thought about it more, it could be maybe a list of items needed to complete a ritual?

The Menu, 72” X60”, Acrylic ink on canvas, 2023

The Menu

72” X60”

Acrylic ink on canvas

2023

(label by Rachel Parikh for my solo show for a painting similarly inspired by manuscripts)

This large-scale painting is an homage to the Devanagari script and the traditional Nepali manuscripts that Shrestha’s artistic oeuvre is inspired by. Produced between the 5th and 19th century, these manuscripts, which typically comprise of Hindu and Buddhist texts, are distinguished by their horizontal composition, neatly and precisely executed text, and exquisitely detailed illustrations.

Shrestha’s curiosity sparked from the vertical orientation of this manuscript. The dimensions and composition work are evocative of traditional Nepali manuscripts, while her large and accentuated calligraphic style challenges the misconception and opinion that Devanagari script cannot be revered for its aesthetic beauty.

The painting itself is a collection of letters written in Devanagari. A reader of Nepali, Hindi, and Sanskrit would recognize the letters, but would not be able to decipher the text because it does not say anything. This is the artist’s commentary on the fact that most Nepali manuscripts in western museums are overlooked and remain untranslated.

The Pink Room

The pink room is titled Devi. It is inspired by my Devi series painting. Here I imagine how museums might celebrate cultures - by celebrating the voices and visuals of people of the culture and by people of the culture.

Here I invite people to enjoy a festive atmosphere, an atmosphere of family, ritual and devotion.

Part of the gold sculpture traveled from the Gardner Museum. This is a second version of the same sculpture. The idea of the sculpture is to take over and transform a space to feel more welcoming for everyone. The flowers in the installation represent the living nature of Newari rituals because our rituals are built into our everyday lives and so the rituals are very much alive.

All photos by Jane Louie